by Martin Waligorski

Photos courtesy of US Navy, Library of Congress, US Air Force

This is the first part of the three-part feature covering the finishes and colours used for the interiors of American-produced aircraft of the World War II era. This part gives general information on the development and the variety of finishes used. In the part two we will cover interiour finishes of the US Army Air Corps / Air Force types. Part three will be devoted to Navy aircraft types. – Ed.

Proceed to Interior Colours of US Aircraft, 1941-45 – Part II

Proceed to Interior Colours of US Aircraft, 1941-45 – Part III

US combat aircraft rank among the better known and documented pieces of World War II technology. So much so that for a time it seemed that at least for a P-51 or P-47 there was nothing more to learn. But, as can be the case with historical research, once in a while a new discovery comes that prompts re-evaluation of what we know about a particular subject. Historic research related to modelling has been full of such development. One that comes to mind is the subject of German fighter camouflages which has gone through a few revolutionary changes during the last three decades, another is the much younger work by Dana Bell and others upon the interior colours of US aircraft.

documented pieces of World War II technology. So much so that for a time it seemed that at least for a P-51 or P-47 there was nothing more to learn. But, as can be the case with historical research, once in a while a new discovery comes that prompts re-evaluation of what we know about a particular subject. Historic research related to modelling has been full of such development. One that comes to mind is the subject of German fighter camouflages which has gone through a few revolutionary changes during the last three decades, another is the much younger work by Dana Bell and others upon the interior colours of US aircraft.

Introduction

On a personal note, I remember researching colour information for a PBY Catalina project back in 1995. To my mind the Catalina ranks among the better documented aircraft subjects out there. I remember posting a note on rec.models.scale asking if RAF Catalinas would have carried colours in the crew compartments according to RAF specs, or if they would be finished according to the original American specs. A simple question it may sound. To my surprise, the discussion that followed revealed that there seemed to be a great white spot in the collective knowledge about what the original American colours would have been in the first place! Time went by and I moved on to other projects, but the sense that something was wrong with the ”Zinc Chromate” interior finish of my model remained. So later on, when I came across Dana Bell’s publications about interior finishes of US aircraft, I knew that his work was right on target – here was the area to be rethinked from the bottom.

As usual, you only find suitable references on a subject after your model is finished: This photo of Jesse Rhodes Waller, A.O.M., third class in a PBY-5 at NAS Corpus Christi, Texas, indicates that the interior colour of the fuselage behind the rear gun blisters was not just Zinc Chromate (Sigh).

Earlier on, everyone simply assumed that all US aircraft cockpits were Interior Green with other internal surfaces in Zinc Chromate. When everybody agrees upon something, it becomes difficult to think beyond the boundaries of common truths. Dana Bell recalls speaking with an aircraft restorer who complained that the Interior Green in his aircraft had aged to a deep dark green. He couldn’t explain what had caused the chemical change, but he proudly announced that he had corrected the colour to the proper Interior Green shade. It simply never occurred to him that the common wisdom was plain wrong.

We know now, contrary to these perceptions, that interiors of US aircraft weren’t always Interior Green or Zinc Chromate at all; in fact some kinds of aircraft were never painted in either colour.

The answers here are complex. It is one thing to prove an old theory wrong, yet another to find out with a degree of certainity what colours were used. In the research trying to determine colours of aircraft interiors, we are still halfway through.

Part of the problem is that ”standards”, even though they existed, were often seemingly loosely defined, which in turn lead to them being widely superceded by practical thinking. Unlike for example the German RLM, USAAF did not seem to enforce its own standards. Paints that did not meet correct colour specifications were used anyway, and often not checked on subsequent batches. There were different paint makers, shortage of certain chemical ingredients, re-formulations to facilitate mass-scale production, and paints mixed locally at the assembly line.

With the risk of stepping right into a wasps’ nest, my intention is to summarize current state of knowledge on the subject and some of the prevailing opinions. This article is a compilation of information I have assembled over recent years form various sources, including books, articles and online discussion forums like rec.models.scale or Hyperscale. Any errors contained herein are the sole responsibility of the author. Additional comments or suggestions are always welcome!

Let’s start with a review of interior paints, colours and finishes used by the US aircraft industry of the period.

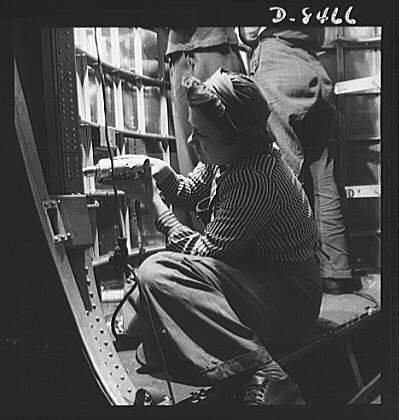

This photo taken at the North American in Inglewood provides a perfect example of the variety of interior finishes employed on but a single aircraft, it this case the B-25. The engine nacelle behind the worker shows two different shades, one on the outer surface of the nacelle, and another on the bulkhead facing the wheel well. The singular cross-member in the middle of the bulkhead partially hiding behind the neck of the worker is in yet another colour, significantly darker than the previous two. The undercarriage strut is painted in silver.

example of the variety of interior finishes employed on but a single aircraft, it this case the B-25. The engine nacelle behind the worker shows two different shades, one on the outer surface of the nacelle, and another on the bulkhead facing the wheel well. The singular cross-member in the middle of the bulkhead partially hiding behind the neck of the worker is in yet another colour, significantly darker than the previous two. The undercarriage strut is painted in silver.

Zinc Chromate

Anyone who has ever read anything on the subject of US aircraft interiors must have stumbled upon the name Zinc Chromate. Yet, do you know what Zinc Chromate is? Understanding it is an essential starting point for the discussion on anything concerning interior colours.

Zinc Chromate is a corrosion resistant agent that is added to certain coatings. Even today, chromate finishes including Zinc Chromate provide superior corrosion resistance. Additionally, Zinc Chromate is highly toxic thus protecting the surface from proliferation of organic matter.

In the aircraft industry of the 1940s, Zinc Chromate was used as an anti-corrosive barrier primer; it could be described as a sort of painted-on galvanizing. It has been developed by Ford Motor Company by the late 1920s, subsequently adopted in commercial aviation and later by the US Military. Official USAAC notes mention successful application of Zinc Chromate primer starting from 1933, but it has not been adopted as standard until 1936.

Back then as well as in the paint industry of today, the term Zinc Chromate does not refer to a paint colour, but rather a protective coating. Therefore, the precise colouring of it is and has not been considered as important as the chemical composition. In the official notes of the period, the name Zinc Chromate is often accompanied by the name of particular manufacturer, thus mentioning Ford Zinc Chromate, DuPont Zinc Chromate or Berry Brothers Zinc Chromate. This means that the actual colour of Zinc Chromate coating may have varied from batch to batch or manufacturer to manufacturer without it being viewed as an issue.

The ’native’ tone of zinc chromate crystalline salt is a bright greenish-yellow. When put into a vehicle with binders to make paint, this colour would be the raw result.

Such raw Zinc Chromate primer would also give a semi-translucent coating, not very opaque like a pigmented paint or lacquer. This property becomes especially interesting when we consider that aircraft factory instructions often called for just one protective coat of primer. As a consequence, the colour of the underlying surface might have a significant effect on the final appearance. For example, raw Zinc Chromate applied on the white background would look yellow, while applied to bare metal aluminium it would look more like apple green.

Similarly, any pigment might be added to the raw paint mixture to go with the Zinc Chromate, thereby modifying the colour. Some of today’s mixtures use iron oxide — giving that rusty red appearance you can often see on prefabricated steel beams in highway and building construction.

So what does all this mean? Perhaps no more than there hasn’t ever been any specification in the industry for a Zinc Chromate colour. This in turn caused alternative designations to pop up in the literature that attempted to describe the colour value of the Zinc Chromate finish – Zinc Chromate Yellow and Zinc Chromate Green being the prime examples. These will be described next.

In US Aircraft industry, Zinc Chromate was in widespread use already at the outbreak of World War II. In comparison, Germany and other axis powers didn’t use it at all, relying on lacquer-based protective coatings – one reason why we never saw any Luftwaffe aircraft in bare-metal finish! The British adopted Zinc Chromate in their aircraft production starting with Martin-Baker M.B.5 of 1945, several years after the Americans.

Zinc Chromate Yellow

In US aircraft use in the 1930s to 1940s, the Zinc Chromate primer was frequently used in the raw mixture yellow tone. This is sometimes referred to as Zinc Chromate Yellow. Like stated above, there is no definitive colour pattern as this may have varied between manufacturers and batches of these primers.

In the immediate pre-war and early war period, the raw yellow Zinc Chromate primer seems to have been dominating.

The raw Zinc Chromate primer was yellow in tone with just a hint of green, as can be seen here. The photograph shows working on the horizontal stabilizer for a Vultee Vengeance dive bomber at Vultee factory in Nashville, Tennessee.

Another example of ”raw” Zinc Chromate primer, this time on the outer skin of a Consolidated B-24 Liberator.

Zinc Chromate Greens

Sometimes, Zinc Chromate was mixed with Lamp Black paste to give a bit more UV resistance (Zinc Chromate is very sensitive to photolitic reactions) and more durability in high wear areas.

Mixing with black gave greener tones, which, depending on the amount of black added could run from apple greens to medium olive greens.

There were many variations in Zinc Chromate Green. Originally, manufacturers were expected to mix raw Zinc Chromate, black enamel and aluminium paste or powder. Several blacks and greys could substitute for the black enamel, and a shortage of aluminium powder/paste caused a reformulation without it in 1942

Some aircraft manufacturers ordered pre-mixed Zinc Chromate Green (Curtiss Cockpit Green, ordered from Berry Brothers, being an example of this).

There is evidence that such variety of shades occurred in the manufacturing practice of US aircraft factories. Where sufficient colour evidence is available, it is possible to find all three colours used on the same aircraft – for example, the yellowish raw colour in the wheel wells, the apple green tones in the gun bays, and the darker green in the cockpit.

A perfect example of Zinc Chromate Green can be seen here. This photo of the internal wing structure on Douglas A-20 bomber. The ribs have been covered with mixed (tinted) Zinc Chromate primer that we will refer to as Zinc Chromate Green.

Untinted and Tinted Primer

US Erection & Maintenance instructions of the period often refer to ”untinted” and ”tinted” primer to describe raw Zinc Chromate primer and the same primer tinted with black. While black was the intended additional pigment, the instructions did not specify the formulation of colours. Therefore it is not unlikely that manufacturers felt free to pick substitute pigments when needed. A Navy memo from 1942 goes even further and recommends using Indian Red, lamp black, or any other suitable indicator to use with a second coat of Zinc Chromate primer to distinguish between single- and double-coated surfaces. In the light of this memo, Vought’s Salmon pink was also simply tinted primer.

Salmon

Salmon was a pale pink-coloured chromate primer used by Vought in production of the F4U Corsair. It was produced by mixing Indian Red pigment with raw Zinc Chromate primer.

The actual tone was reddish orange.

Colour sample

- As Salmon was a mixed primer, claiming an exact colour shade for it would be misleading. However, the FS colour match could be somewhere between FS 32276 and 32356.

Cockpit Green Colours

While the raw yellow-tone Zinc Chromate was technically a very effective anti-corrosion primer, it was found to be less suitable for crew areas. The bright interior surfaces coupled with bare metal surfaces underneath caused excessive glare and eyestrain for the crews.

Actually, there was a directive issued by the USAAF during the war specifically prohibiting the use of plain Zinc Chromate primer in crew occupied areas.

Selecting the appropriate mixture to replace raw primer in the cockpits has been initially left to the manufacturers. In most cases, various mixtures of Zinc Chromate and black were the most readily available replacements, resulting in shades that are sometimes referred to as Light Green or Cockpit Green. The ”formula” probably did vary and some manufactures may have used commercially available paints that were closer to Bronze Green or even ANA 612 Medium Gree

The name Cockpit Green has gained the official status only briefly in the 1943 ANA (Army-Navy Aircraft) colour agreements, where green-tinted Zinc Chromate was briefly called Cockpit Green before the final name Interior Green was assigned as described below. However, despite an official colour chip being provided in the ANA standard, it is believed not to be widely adopted, especially as the standard proved short-lived and the instructions usually called for existing paint stocks to be used up before shifting to a new colour.

Interior Green (ANA 611)

In September 1943, US Navy specified a Zinc Chromate and Lamp Black mixture to a colour standard, which became a standard ANA 611 Interior Green. The instruction was an after-the-fact attempt to standardize a variety of greens being used to paint crew areas.

The formal name Interior Green came along with ANA Bulletin No.137 issued at the time, which designated black-tinted Zinc Chromate primer as ANA 611 Interior Green. Of note is that the Interior Green was no longer to contain aluminium paste.

In time, this colour’s use and mixture became more widespread than the others. However, the eventual transition period leaves a lot of space for speculation. Because of the previous (and mounting up) ambiguities in colour specifications, it might have happened that the standard Interior Green didn’t look very different from any formula that a manufacturer had used before, and today it would still be difficult to say which formula was used to make a sample.

Colour sample

- FS 34151 is believed to closely match ANA 611 Interior Green

Bronze Green

Like Zinc Chromate, the term Bronze Green is generic and describes a dark green finish obtained using oxidized bronze as a pigment. Still used today, the term is another example of a name designating a chemical composition becoming the name of a colour. Many people associate the word Bronze with red-brown colour, but this is not the case for Bronze Green. The pigment itself contains mostly Copper Carbonate, a compound responsible for the green patina often seen on old Bronze monuments.

Bronze Green-based colouring has been widely used in ceramics, producing good-looking medium and green glazes such as one shown above.

Dana Bell was the first to unveil the existence and use of these colours in Air Force Colors, Vol 1 almost twenty years ago. Although it is now generally agreed that Bronze Green was widely used for cockpits, we still cannot claim to have the answers to all the questions about Bronze Green and its successor colour – Dark Dull Green.

Bronze Green was specified as standard for U.S. Army cockpits in the late 1930s, but was also used by the Navy. Grumman and Republic seem to have used Bronze Green extensively, possibly more than other manufacturers. This may be attributed to both companies being located in the Long Island area, subcontracting paints form the same sources.

Bronze Green has been confirmed for the seats of North American P-51 Mustangs – which were probably subcontractor-supplied. Pilots’ seats and many of the internal fittings in the Boeing bombers were also painted in this colour.

Bronze Green could have been used also for forward anti-glare panels on silver aircraft. For example, Army maintenance instructions called for its use on B-18s.

Colour sample

- Establishing a reasonable FS match for Bronze Green is not easy, different sources have quoted FS 24050 or 24052. What is known is that it was a lacquer with semi-gloss surface finish.

Dark Dull Green

Dull Dark Green was an outgrowth of Bronze Green introduced in September 1942. When introduced, Dull Dark Green was intended as a substitute/replacement for Bronze Green. There has been much confusion about the difference between the two colours. Without being conclusive, it would appear that the shades were very similar, with Bronze Green being slightly darker and semi-gloss. The sheen of Bronze Green was one reason why the all-matt alternative was sought.

When issued, the Dull Dark Green was to be used for tactical aircraft with enclosed crew cabins – i.e. bombers. However, it seems to have gained much greater popularity than intended by the ANA officials. The use of Dull Dark Green can be confirmed for cockpits of F4U Corsairs, later-production Avengers, P-51s, and P-47s as well as forward crew areas of B-17s, B-24s and B-29s. Interestingly, the use of Dull Dark Green in fighters ignored the general specifications calling for interior green in those aircraft.

Dull Dark Green was no longer included in the 1943 ANA colour standard, but the colour was still used. For example, later Erection & Maintenance manuals for the P-51D called for Dull Dark Green for certain cockpit components like seats.

Colour sample

- FS 34092 seems to be a reasonable match for Dull Dark Green, with a comment that the original colour was slightly darker.

Grumman Grey

Grumman was unique to use their own, non-standard primer on all Grumman aircraft. In modern literature it is often referred to as Grumman Grey.

Colour sample

- FS 36440 is believed to be a reasonable match for Grumman Grey.

Aluminium

Aluminium (”Aluminum” in US English) paint finishes have been widely used in the aircraft industry since the 1910s. Aluminium paint was created by mixing the appropriate clear carrier paint with aluminium powder or paste. Unlike other paint pigments that are finely ground powders, aluminium powder consists of tiny ”flakes”. As the paint dries on the surface, these miniature flakes flatten out over their underlying surface forming a superb protective layer. That action is what made aluminium paints so valuable as airplane finishes. On fabric surfaces, aluminium finish had also an added value of making fabric less brittle and longer lasting. Last but not least, at the time no other pigment provided a lighter yet opaque painted finish.

Depending on the application, the carrier paint could be clear dope, clear varnish, lacquer or oil-based primer.

The first aircraft to take advantage of Aluminium dope were Zeppelin airships. In 1912 the British Cellon company commenced commercial manufacturing of Aluminium dope, and from then on it rapidly became a worldwide standard for aircraft finishes. Aluminium dope was used as a topcoat finish, but also as primer.

Aluminium lacquer has been the overall finish for cockpits of early yellow-wing F2A Buffalos and F4F Wildcats, possibly also other pre-war Navy types.

One area were aluminium lacquer was frequently used was undercarriage legs and struts. Please note the considerable difference in shine between the painted leg and fork, cast aluminium alloy wheel hub and exposed steel of the oleo. The leg (shown before) is a front undercarriage of the B-25 Mitchell.

Distinguishing between Aluminium lacquer and bare metal finish can be confusing. Although pure aluminium is resistant to corrosion, aluminium alloys initially used in airframe production were not. Thus, metal aluminium elements required priming, initially with oil-based primers and then with Zinc Chromate. The situation changed in early 1930s with the adoption of aluminium alloy sheet named Alclad. Alclad was an aluminium alloy sheet covered externally with thin layers of pure aluminium as an anti-corrosive barrier. It is this solution that made it possible to dispense with painting of the airframes after 1943. In principle, this development had nothing to do with the use of Aluminium Lacquer, which can be seen on various internal fixtures of aircraft throughout the discussed period.

View of the wing brace assembly of the B-25 Mitchell shows a mixture of bare Alclad and Zinc Chromate-covered components used during production.

Olive Drab

The US Olive Drab was an outgrowth of RFC green, the WWI aircraft colour used by the British. Although primarily an outer camouflage colour, the use of Olive Drab is documented in some cases also for cockpits – like on P-38s and L-4s.

Olive Drab has also gone through some significant evolutionary changes. During the period 1938 – 1945 there were alt least three official Olive Drab specifications for the USAAC/USAAF.

- Pre-war Olive Drab No. 9

- Dark Olive Drab 41

- Olive Drab ANA 613

Prior to World War II, the standard Olive Drab shade of the USAAC was called Olive Drab No. 9.

In 1940, when Army and Navy got together on the ANA standard it was decided that No. 9 was too light, and should be substituted by Dark Olive Drab. The ”new” paint (which actually had been available since 1932) was designated Dark Olive Drab 41.

It would have seemed that the standard had been set, but this was not to be.

Olive Drab 41 was originally a mix of seven different pigments. When the war started it soon turned out that that massive amounts of Olive Drab paint were going to be needed, and paint manufacturers began to look for ways to reduce the number of ingredients. Additionally, Cadmium was widely used as a paint stabilizer. However, cadmium was a scarce resource and the paint industry found itself in competition with the steel industry that required cadmium as a hardener for production of armour plate. The result was that cadmium was removed from paint mixes. As a result, the wartime Olive Drab 41 might only have a couple of different pigments in it, the formulation varying between different paint manufacturers.

All this has resulted in paint that proved (knowingly) much less stable in field conditions. New aircraft matching (or not) specification colours at the door of the factory could demonstrate quite dramatic changes of colour once deployed in the field. Different batches of paints would fade at different rates to different base colour. For example, pilot of the 14th Fighter Group operating Lightnings in North Africa have reported that under African sun their early-model P-38s turned into bright purple!

Based on the analysis of the remains of crashed aircraft in the ETO, German researcher Has Ploes claims that there were at least two variations of the Olive Drab paint. Originally both paints would have had almost the same shade but one of the two paints weathered very quickly to a reddish shade. This paint was used by Douglas on A-20 Bostons and by Boeing on the B-17Gs. The other paint, much more steady and resilient to ageing, has been found on crashed P-47s and P-38s.

Further attempt at simplification on the part of officialdom came in March 1943, with the ANA 613 standard, which unified the Army and Air Force Olive Drab to a single shade following the Army specification, which was lighter than Olive Drab 41.

Although officially affected by ANA directives, USAAF did not display much interest in this new paint. It would appear that they just chose to ignore the chips, and ordered paint manufacturers to continue to match the Dark Olive Drab 41 paint chips. Thus Dark Olive Drab 41 was still being produced and used in production of camouflaged aircraft throughout the war.

One documented adoption of ANA 613 paint was were the very late (post mid-1944) Douglas A-20G/Hs and J/Ks produced for the Soviet Union. Machines produced for lend-lease were camouflaged throughout the war, and Douglas was forced to switch from Olive Drab 41 to a lighter shade of Olive Drab, which can be assumed to match to the ANA613 chips.

Colour sample

- There seems to be a consensus in the model paint industry about adopting FS 34088 as the correct shade for faded Olive Drab 41. Other reasonable matches for Olive Drab (from dark, factory fresh finish to bleached and weathered) could be in the range FS 34064 through 33070 to 34088

Medium Green

In the initial war period, the Army specification for a standard topside camouflage was Olive Drab 41 with Medium Green 42. Medium Green was to be used in irregular blotches on leading and trailing edges of wings and stabilizers and vertical tail to disrupt the contours of the airframe. This pattern lasted throughout 1942, but was generally dispensed with later.

Like Olive Drab, Medium Green has gone through similar evolution of designations:

- Medium Green 42

- Medium Green ANA 612

It is not known for sure how much Medium Green was used for interior finishes. Several Army instructions dated as long as end-1943 called for Medium Green finish on interior portions of cockpits that were subject to direct rays of the sun. Bell might have used a variation of Medium Green for the cockpits of P-39 Airacobra.

On a side note, Medium Green appears to have been very similar in shade to Dark Dull Green, so distinguishing between the two based on photographic evidence may be very difficult.

Colour sample

- FS 34092 seems to be a reasonable match for Medium Green, with a comment that the original colour was slightly lighter in shade.

Insignia Red

The use of Insignia red has been documented on the internal flap surfaces of SBD Dauntless.

The pre-war US Army Insignia Red was a vivid bright red, and was not suited well for camouflage purposes. During the colour unification work performed by ANA during the initial months of the conflict, RAF Insignia Red was found to be much less intense, of darker hue and generally better suited for the purpose. Ironically, the same month the RAF colour was accepted by the USAAF, red was eliminated from the insignia of all US combat aircraft.

Colour sample

- FS 31136 is a match for Insignia Red.

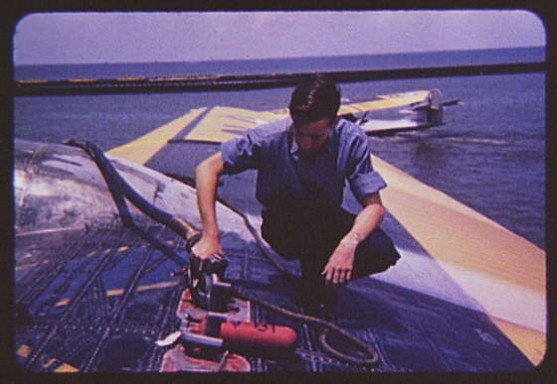

A word of caution. However complete the above colour review might be, you can always expect to find the unexpected, like this vivid red colour beneath the fuel tank cover on upper wing of the PBY-2.

Continue to Interior Colours of US Aircraft, 1941-45 (Part II)

References

Literature:

- Dana Bell – World War II US Aircraft Interior Colors, Fine Scale Modeler October 1997

- Dana Bell – Air Force Colors, vol. 1-3

- Robert D. Archer – The Official Monogram US Army Air Service & Air Corps Aircraft Color Guide

- John M. Elliot – The Official Monogram US Navy and Marine Corps Aircraft Color Guide

- Doll, Jackson, Riley – Navy Air Colors, Vol. 1, 1919-1945.

- Dave Klaus – Color Cross-Reference Guide

- Bert Kinzey – In Detail and Scale

- Dana Bell, Lee Kolosna, William Reece, Larry Webster – various postings and articles

This article was originally published in IPMS Stockholm Magazine in January 2004.