by Martin Waligorski

Photos courtesy of US Navy, Library of Congress, US Air Force

This is the second part of the three-part feature covering the finishes and colours used for the interiors of American-produced aircraft of the World War II era. Please refer to part one for general information on the development and the variety of finishes used. This part two covers interiour finishes of the US Army Air Corps / Air Force aircraft. The forthcoming part three will be devoted to Navy aircraft types. – Ed.

Back to Interior Colours of US Aircraft, 1941-45 – Part I

Proceed to Interior Colours of US Aircraft, 1941-45 – Part III

In the first part of this feature (see Interior Colours of US Aircraft, 1941-45 – Part I) we have discussed the protective finishes used in US aircraft production of the immediate pre-war and World War II period, and the evolution of colour shades and specifications used in that production.

In this installment we will go more specifically into interiour finishes of selected US Army Air Corps / Air Force types. It is perhaps worth pointing out again that the author’s intent is summarizing the current state of knowledge on the subject, knowing that the picture may in many cases be somewhat blurry and incomplete. The information for the article has been assembled over recent years form various sources, including books, articles and online resources. Although the author has done his best to differentiate between established facts and opinions, the presented information cannot be considered as definitive. Future research – and there remains a lot to do! – may also introduce changes and additions to our current views.

Any errors contained herein are the sole responsibility of the author. Additional comments or suggestions are always welcome.

USAAF interior colours

When considering the popular Air Force types, one should keep in mind the truly huge production series of these aircraft. Because of the demand, many aircraft types were also mass-produced in multiple plants, most often very distant apart. It is documented that the production standards on all levels could vary wildly between them -a well-known fact that made the B-24, for example, a maintenance nightmare. To get a better idea, let’s list the manufacturing locations of the most-produced aircraft types:

Lockheed P-38 Lightning

Produced by Lockheed at Burbank, California (LO). P-38Ls also produced by Consolidated-Vultee Aircraft Corporation at Nashville, Tennessee (VN)

Bell P-39 Airacobra / P-63 Kingcobra

Produced by Bell Aircraft Corp. at Buffalo, New York plus a newly-erected plant in Atlanta, Georgia (both designated BE)

Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk/Warhawk

Produced by Curtiss-Wright Corp. at St.Louis, Missouri plus two newly-built plants in Buffalo, New York and Columbus, Ohio (all designated CU)

Republic P-47 Thunderbolt

Produced by Republic Corp. at Farmingdale, New York (RE) and a new factory at Evansville, Indiana (RA). Additionally, P-47Gs were produced by Curtiss-Wright Corporation at Buffalo, New York (CU).

North American P-51 Mustang

Produced by North American Aviation Incorporated at Inglewood, California (NA) and a new factory in Dallas, Texas (NT).

Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress

Produced at Seattle, Washington State (BO), Douglas, Long Beach, California (DL), Lockheed Vega at Burbank, California (VE)

Consolidated B-24/C-87 Liberator

The production scheme of the B-24 deserves special description. In order to meet the projected demand for the B-24, in early 1941 the government established the Liberator Production Pool Program. It would involve no less that five major factories:

- Consolidated-Vultee mother factory at, San Diego, California (CO)

- New Consolidated-Vultee plant in Fort Worth, Texas (CF)

- Douglas at Tulsa, Oklahoma. (DT)

- Ford Motor Company at Willow Run near Detroit, Michigan (FO)

- North American Aviation at Dallas, Texas (NT)

Although the three primary manufacturers in Sand Diego, Willow Run and Dallas were assigned separate version designations of B-24D, E and G respectively, each plant in the pool would often use sub-assemblies and components provided by the other members. In case of the Liberator, the standardised version designation system proved inadequate to tell maintenance people which factory was really responsible for any given plane, the Liberator becoming widely known for its maintenance and spare parts problems. The general rule seemed to be that the manufacturer code assigned to a particular aircraft corresponded to the factory that was responsible for its final assembly. For example, the version of the Liberator that underwent primary manufacture at Consolidated San Diego was designated B-24D. When the B-24D was completely assembled at San Diego, it was designated B-24D-CO. However, the San Diego plant also shipped parts and components of B-24Ds to Consolidated Fort Worth and to Douglas Tulsa for final assembly. B-24Ds assembled by these plants were designated B-24D-CF and B-24D-DT respectively. It doesn’t take a scientist to realize that all this would have a major impact on the variety of interior finishes in these machines.

B-24Es at the Willow Run assembly line. Images such as this give a hint about the scale of production programme for the B-24. Yet this picture has been taken only in 1942, when the Liberator Production Pool Program was but a year old.

The general wisdom of this summary is that it would be outright strange if supplies of paint or paint application standards would remain unaltered throughout so long production runs and geographic distances.

With the abandonment of camouflage in late 1943, airframe primer was often, but not always, also dispensed with. However, since subcontractors ran on different schedules and could to a degree set their own standards for surface finishes, it was not uncommon to see partly primed airframes on natural metal aircraft. However, cockpits and crew areas generally continued to be painted as an anti-dazzle measure throughout the war.

Bell P-39 Airacobra

Despite its massive production numbers, this aircraft appears to be relatively poorly documented. Available colour photos show Interior Green and Bronze Green for cockpits; Interior Green, Zinc Chromate Yellow or Aluminium lacquer for wheel wells; nose undercarriage legs painted with Olive Drab and Interior Green; wheel hubs in Interior Green and natural metal. It would seem that the jury is still out for this aircraft.

According to Bert Kinzey in his Detail and Scale book on the P-39 the interior colour used by Bell was called just Bell Green. That included the cockpit, the wheel wells, the landing bay doors and the undercarriage struts. There has been a lot of discussion as to what exactly Bell Green was. The suggestions go towards something similar to Medium Green.

Based on the analysis of a preserved Lend-Lease P-39Q-15, the inside of the wheel wells was painted in Zinc Chromate Yellow for the wing part and Olive Drab in the part overlapping the lower fuselage, apparently a result of separate painting of the subassemblies at the factory. The undercarriage legs and internal faces of wheel covers were Interior Green, with smaller actuating arms finished in Bronze Green. Additional piping and wiring was painted in Aluminium lacquer.

Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress

Early B-17s had overall Zinc Chromate Yellow interiors, Bronze Green cockpits and navigator’s stations, and Aluminium lacquer bomb bays.

For F and G model B-17s, the general rule for ”control cabins” is Bronze Green. Instructions identify the ”control cabin” as the nose section containing the bombardier and navigator, the cockpit including the pilots and top gunner/engineer, and the radio room. Later official specifications for the B-17F revised in August 1944 called for Dull Dark Green in the same areas. Some Douglas-produced B-17Fs possibly had Interior Green control cabins

The same 1944 document calls for use of Bronze Green on exterior anti-glare panels of uncamouflaged aircraft. It remains controversial if this instruction was ever followed in B-17 production, most colour photos of the B-17s showing Olive Drab anti-glare.

Inner fuselage sides in the nose, cockpit and radio room were covered with green canvas padding. The cabin floor was made of varnished plywood. In high-traffic areas, floors were covered with black rubber mats anti-skid purposes – in the waist, the radio room and the top turret area. The floor in the pilot/navigator cabin was left in natural metal. Pilot and navigator seats were most probably Bronze Green.

Aft of the radio room, the fuselage interiors of many early-production B-17s were painted Zinc Chromate Yellow. Later versions of the aircraft, camouflaged as well as natural metal were often left in bare metal with Zinc Chromate Yellow or Zinc Chromate Green bulkheads and longerons. Note that the waist-gun areas were also left in bare metal, presumably because there were no glare problems for the gunners there.

Rear fuselage of the B-17F at the Long Beach assembly line showing the area near waist gun stations. This photo provides a prime example of bare metal interior with Zinc Chromate Green longerons. Some of the bulkheads further aft are also green, while those closer to the photographer are left in natural metal.

The prevailing colour inside gun turrets seems to have been Dull Dark Green, on later models also flat black.

Among the areas left unpainted were also bomb bays and bomb bay doors, although some sources state Neutral Grey for camouflaged aircraft.

Wheel wells are believed to be usually painted Interior Green.

Another photo of a tail of a camouflaged B-17F Flying Fortress at the Douglas factory in Long Beach. The fuselage construction illuminated by flash behind the workes’ heads shows that there were at least two different colours of primer used. Another mystery.

Consolidated B-24 Liberator

Like the B-17, late-model B-24s are believed to have used Dark Dull Green in the forward crew areas, with remainder of the fuselage and waist-gun areas left in natural metal. Early camouflaged models had Zinc Chromate Yellow interiors.

Many photos of the camouflaged B-24s show Neutral Grey undercarriage legs, doors, and wheel wells.

Another myth that awaits revision is that of black instrument panels on these bombers. Examination of some of the preserved B-24s revealed that the instrument panels were dark green rather than black.

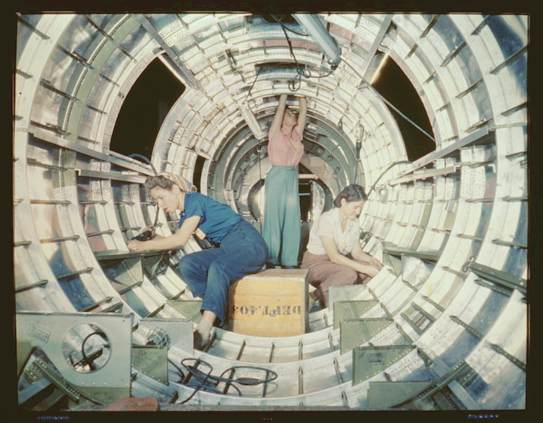

B-24E Liberator fuselage assembly at Willow Run, 1942. This photo shows the mid-section of the fuselage with oxygen flask holders visible at the upper decking. A few colour photographs from the same photo session appeared in the December 1944 issue of National Geographic, showing clearly that the overall colour of the interior was Zinc Chromate Yellow.

Colour photo of the same fuselage section of a C-87 transport at another Consolidated plant at Fort Worth, Texas. Although boths photos have been taken around the same time and at the similar stage of assembly, this one shows a bare metal finish.

Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk/Warhawk

Unlike some other manufacturers (like Boeing), Curtiss painted their aircraft directly at the factory.

The cockpit of the P-40 was Curtiss Cockpit Green, which was the Berry Brothers’ (a local paint vendor) approximation of Interior Green. Reportedly it was a little browner than Interior Green.

The scalloped cutouts inside the fuselage windows aft of the cockpits on P-40D to M models were usually painted the same as the camouflage colour. As the rear windows could be easily detached for re-painting, most field repaints were also performed this way. Earlier P-36 Hawk production practice and some photos of the early P-40D and Es indicate that Curtiss could initially have used a different colour for the cutouts. It could have been the same as the cockpit colour, but the author was not able to find any positive confirmation of this.

Rear view windows behind the cockpit of the P-40 could be easily detached for painting. Consequently, the majority of images show the camouflage pattern to continue under these windows.

The wheel wells had canvas covers similar to that on the Bf 109E. These were in drab canvas colour with brass zips and fasteners.

Lockheed P-38 Lightning

Recent research claims that early production P-38Es and F-1s had Olive Drab cockpits.

Later down the production line, for the P-38F to H, the colour was changed to Interior Green. Instrument panels, control columns, rudder pedals and electrical boxes were all black.

Some evidence suggests that some (possibly subcontracted) components, notably pilot seats and the rear armour plate attached to it continued to be delivered in Olive Drab through a long time after the transition to Interior Green was made. With the arrival of the P-38J, the shape of internal armour plate was modified – and it seems to have received Interior Green finish matching that of the rest of the cockpit.

Wheel wells and interior of the well doors of camouflaged aircraft were painted in Neutral Grey with selected structural elements in Zinc Chromate Yellow. Undercarriage legs were painted in Aluminium lacquer.

Martin B-26 Marauder

Cabin interior colours of B-26 Marauder remain something of an enigma. About the only source for the information contained herein is the examination of the nose of B-26B-25-MA Flak Bait which is on display in original condition at the National Air and Space Museum, Washington , DC. In the above photo, the view of the forward ring of the fuselage to which the clear perspex nose is attached indicates at least that (a) the cabin interior of this B-26 was painted and (b) the colour was not black.

Martin seems to have not used Zinc Chromate primer very often. Most interior parts were left in bare metal or painted in clear lacquer. Only a few components like steel parts and rudders were painted in Zinc Chromate Yellow.

Production standards of the B-26 have not yet been sufficiently researched. The National Air and Space Museum has the forward fuselage of the famous B-26B-25-MA Flak Bait, which is the basis of the following colour information. In the cockpit, everything above the lower canopy edge was painted flat black paint, as was the floor, armour plating, and crew seats. Fuselage sides in crew areas were padded with drab-coloured insulation material.

Interior of the fuselage including the bulkhead aft of the cabin seats was unpainted aluminium with black floors and walkways.

The wheel wells were finished is Aluminium lacquer, with selected fixtures in Zinc Chromate Yellow. Photos exist of camouflaged B-26s that show Neutral Grey on the undercarriage legs and inner surfaces of gear doors.

North American B-25 Mitchell

A wing brace assembly for a B-25 bomber prepared for the assembly line of North American Aviation at Inglewood, California. The picture shows the use of both primed and unprimed components in the wing assembly. The primer appears to be ”raw” Zinc Chromate.

B-25 remained in production throughout the entire war, so there have been a lot of variations.

Based on the Erection & Maintenance instructions for B-25C, early B-25 models B, C and D had Bronze Green crew cabin. Instrument and other panels were black. Some photos show crew seats in unpainted aluminium with drab seat cushions.

Zinc Chromate Yellow was used other fuselage interiors, including its entire rear part.

Opinions vary concerning the finish of cockpit floors and crew walkways. Some say it was Yellow Zinc Chromate, others unpainted aluminium, others Green Zinc Chromate.

Series of photos of new B-25Cs prepared for the first flight at the North American factory in October 1942 suggests some dark grey and green elements at the aft bulkhead of the bombardier’s compartment. The green could be a mixed primer or Bronze Green. Other photos from the same session show Bronze Green fittings on the same bulkhead as well as black decking forward of the instrument panel.

Interior of the engine nacelles, engine cowlings, undercarriage bays and doors were all finished in Zinc Chromate Yellow.

Insulating material was dyed to match the interior finish coating for that compartment – Bronze Green or Chromate Yellow.

Interior of the bomb bay and bay doors was painted in Aluminium lacquer.

Later models of the B-25 went to overall Bronze or Dull Dark Green in the cockpit with natural metal rear fuselage and Aluminium lacquer wheel wells.

The final and the most numerous J model standardised on Interior Green for the cockpit and the rest of the interior.

Another shot from the B-25 assembly line shows the partially cowled Wright R-2600-13 Double Cyclone engines. Noteworthy is the blue-grey colour of the crankcase cover.

North American P-51 Mustang

In the beginning, the P-51 was built exclusively to the British specifications. In the Mustang Mk. I production, North American reportedly used colours that were substitutes of the official colours of the RAF.

When the P-51B came about, it was probably painted Dull Dark Green throughout the cockpit.

The June 1944 Structural Repair Manual for all version of the P-51 calls for overall Interior Green in the cockpit, in the area extending from the instrument panel to the back of the canopy. An exception from the rule was that areas not normally visible required no finish coat. Instrument panel was specified as Instrument Black.

According to the same source, pilot’s seat and the anti-glare forward decking were to be painted Dull Dark Green. However, there are clues indicating that this colour may not have been used on any on the items. Based on the inspection of preserved aircraft, Dana Bell claims that at least some of the seats of the P-51 were painted Bronze Green rather than Dark Dull Green. Likewise, many wartime colour photographs consistently show Olive Drab in the anti-glare area.

Another subject of long-going controversy is the colour of the cockpit floor, which in P-51 was made of plywood. Erection and Maintenance instructions for the P-51D specify all wood floor areas to be covered in black non-skid surfacer purported to be a mix of silica sand and matt black paint, the kind of finish that was also used for wing walks. Metal floor areas were to be left in bare metal finish.

The December 1944 update of Erection & Maintenance Manual for the P-51D follows the same description with the exception of anti-glare decking inside the canopy which was to be painted black.

Similarly to other aircraft types, the camouflaged P-51 most probably had wheel wells painted in Neutral Grey. On later-production natural metal aircraft, the wheel wells were Interior Green. Additional piping and wiring inside the wheel well area was painted in Aluminium lacquer.

A rather extremely underexposed photo of an Allison-powered, cannon armed P-51 at the assembly line in Inglewood taken some time during 1942. One of the few elemets that can actually be seen is the mixed Zinc Chromate wheel well. Like many other American aircraft, early Mustangs were built exclusively to the British specifications, but it is most likely that primer finishes followed the Amercan practice all the way.

Northrop P-61 Black Widow

Factory instructions for the P-61 stated that all exposed interior surfaces of the pilot, gunner and navigator compartments were to be finished in Northrop Cockpit Green, another factory-specific variant of Interior Green. Instrument panels were to be finished in flat black. Interior surfaces visible from the outside carried the same finish as the outside of the aircraft.

Zinc Chromate Yellow was used as general finish of all unexposed interior surfaces of the P-61. Even the wheel wells were finished in this colour. Two exceptions were the inner surfaces of engine cowlings and the firewalls which were left unpainted.

Republic P-47 Thunderbolt

The subject of cockpit colours of the P-47 seems to have thus far defied conclusive analysis. Surviving P-47s and contemporary photos show a dark green shade in the cockpit, similar or possibly equal to Dull Dark Green. This is in contrast with the available Erection and Maintenance manuals which invariably call for green-tinted primer in cockpit areas.

The 1944 Erection and Maintenance Instructions covering P-47C, G and D state that ”cockpits shall be finished with one coat of tinted zinc chromate primer to eliminate glare resulting from untinted primer.” As can bee seen, the use of ”tinted primer” is not consistent with the Dark Dull Green found in other evidence.

Perhaps an explanation is to be found in the formula of tinted primer given in the above manual. Nowhere in the above document is the tinted Zinc Chromate specified to match ANA Interior Green. Instead, the specifications include a rudimentary mixing formula, described as one gallon Black to one gallon Yellow Zinc Chromate primer. The formula is probably an error. If the intended colour was to be Interior Green, the document should have stated 1/10 gallon Black to 1 gallon Zinc Chromate, consistent with other Erection and Maintenance documents of the period.

A possibility remains that Republic followed the instructions to the letter, obtaining some sort of black-green colour for the cockpit areas. Other hypotheses claim that the colour used could be Bronze Green or Dull Dark Green. Another mystery

Another conventional wisdom states that Curtiss-built P-47Gs differed from Republic-build P-47Ds by having Interior Green (actually, Curtiss Cockpit Green) in the cockpit and wheel well areas. However, this does not seem to be consistent with examination of wrecked P-47G parts, which show Dark Dull Green in the cockpit.

Since there were less than 200 P-47Gs made and they were only used for training in the US, this controversy is of limited interest to modellers, which would usually be interested in Republic-made Thunderbolts.

According to the Erection and Maintenance manuals, the fuselage decking under the bubble canopy of the P-47D from the windscreen to the area aft of the cockpit armour plating, was to be painted Dark Olive Drab 41, the same colour being specified for the anti-glare area of the forward fuselage. Armour plating was specified to the same colour as the interior finish of the cockpit.

Another yet unresolved mystery is the turtleback area beneath the rearmost cockpit window of the razorback versions. Many variants have been called for, but the most likely choices (based on the available contemporary colour photographs) are Olive Drab for the early camouflaged aircraft, and some kind of medium grey further down in the production.

According to factory instructions, the fuselage decking inside the canopy on bubbletop Thunderbolts was to be painted in Olive Drab, with the inside of the canopy framing in flat black. The rear armour plate in the cockpit was to be painted to match the cockpit interior colour.

Interiors of P47 aircraft cowlings were natural metal. The aluminium in this area was anodised giving a darker and very dull greyish appearance. The engine firewall was left unpainted. Engine mounts were primed in Zinc Chromate Green.

All other interior surfaces of the fuselage with exception of the firewall were finished in Zinc Chromate Yellow. This included also wheel wells, undercarriage covers and armament compartments in the wings.

Undercarriage legs were painted Dark Olive Drab 41 on camouflaged aircraft. This practice continued over to at least some natural metal machines. At some point in production the requirement seems to have changed to allow an Aluminium lacquer finish to be used.

Armourers using hoist to laod bombs into the bomb bay of Douglas A-26 Invader, somewhere in England, 1944. The Invader is one of the aircraft not covered in the above review, yet I find this photo interesting enough to include it here. A-26 production was initiated late in the war, when most of the US combat types already left the factories in natural metal. This aircraft also shows natural metal finish of the fuselage, but as can be seen the bomb bay was painted.

Continue to Interior Colours of US Aircraft, 1941-45 (Part III)

This article was originally published in IPMS Stockholm Magazine in February 2004.