Group Project of a Lifetime

by Moreno Bartolucci , Associazione Modellisti Chiaravallessi

The idea to build a 1/25 scale model of the Abbazia of Chiaravalle was born quite in the same instant as the inception of the Associazione Modellisti Chiaravallesi club back in 2002. So it is very difficult for us imagine our Association without this model. It has always been there; previously in our dreams and fantasy, then in the life of the club. It has been finished thanks to the ability, determination and patience of a number of our members, in not less than 33 months of hard work.

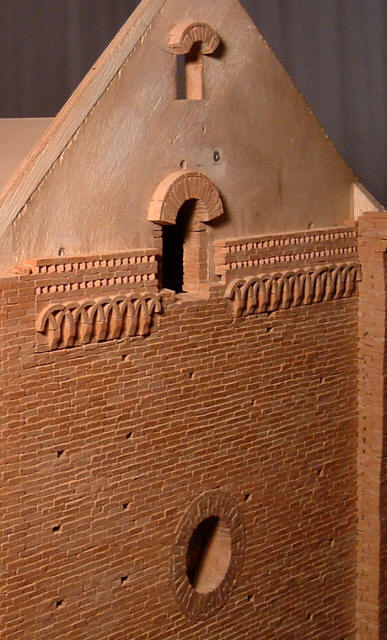

In our city, Chiaravalle near Ancona in middle Italy, not far from Adriatic Sea, everybody’s life is in some way connected with Abbazia di Santa Maria in Castagnola. She was there before the city came to life, when the Bernardine friars of Cistercense order of St. Bernard of Clairvaux built it in the 11th century, in the middle of what was then an uninhabited forestland. The city emerged at a later date, for the very reason that the Abbazia was there. Today the monument resides in the heart of the city. It’s impossible not to admire this magnificent building, regardless of your religious convictions.

As a club we were strongly determined to put the first stone of a Musem of Modelling in our city. To compel the borough authority to support the idea, what could be better than to produce a model so good, so big and so admired by everyone so that the authority would have to designate a public display space!

The Planning

The planning of the project was in many ways as demanding as its construction. Considering the fact that most of us are “classic” modellers: plastic static modellers, ship model builders, R/C airplane modellers and so on. Unfortunately, nobody initially had any idea how to build a replica of a church!

The first requirement was the workshop space: where to erect and keep a model measuring 2,5 x 1,5 metres. This first problem has been brilliantly solved wit the help of Chiaravalle’s Mayor, who allowed us to use a space inside the Abbazia itself. Since January 2003, we established our field base in Sala Monaci, the southern big hall, which the Bernardines used as a scriptorium – rewriting ancient manuscripts during the Middle Ages. What a luxury of building a model in a historic place of such ancestry, and with the first-class reference material all around your workshop!

One the modellers in our group has a relative who several years ago got a master’s degree in architecture with a thesis about the Abbey. He was very kind to pass the set of all the drawings in 1/100 scale that he produced for his degree. Bringing them to 1/25 scale was a simple matter of four-fold magnification.

The Structure

At this stage we have already discarded an option to produce a wooden replica with painted-on brickwork as too easy and uninspired. We wanted a realistic-looking masonry and for the time we considered the use of chalk blocks or plaster of Paris. In the end we settled for nothing less than a real thing, bricks. We wanted to produce bricks exactly like the real ones, only 25 times reduced in size, to mount on a plywood chassis.

The main body of the model was then produced from plywood. In the beginning we mounted the plywood panels on an angular metal frame. Once the assembly of the structure was completed this was however discarded because we realised that it was a complication without any real increase in stability in comparison to a working plywood chassis.

The sheer size of the model was now readily apparent. We manufactured a six-wheel trolley with welded metal frame and wooden top to carry the model. We did the job thoroughly realising that the trolley would be the model’s final base; although the model was still moveable at this point the brickwork would add a lot of additional weight making the model difficult to move around. In the base we made a rectangular aperture through which it is possible to look inside the church, for inspection and to facilitate further construction.

The Brick Machine

The obviously big problem was producing the bricks, and not just some of them but an estimated quantity of 200,000 pieces. To be able to do it we needed a brick mould, one which would enable us to produce bricks in quantity and to consistent standards.

We thought at a rectangular grid produced of steel sheet would be our brick mould. This first grid had fixed dimensions and enabled to produce about 100 pieces each time.

The raw material chosen for the bricks was the same as that of the real ones, red clay, after forming to be fired at 1000° in an oven for burning ceramics. We made a search for appropriate clay material and found it at Deruta, near Perugia, where traditional ceramics and clay manufactures are based. In all, we used 235 kg of clay. Each brick measures 10x15x4,5 mm.

Back at our brick-moulding tool, the soft clay was laid on the mould with a spatula. Then it had to be left to dry before the bricks could be removed and fired in the oven. The problem with a fixed grid mould was removing the bricks from the mould, the main problem being that the bricks stuck so hard to the wooden bottom that most of them had to be broken off to yield, despite being ”only” dried at this stage.

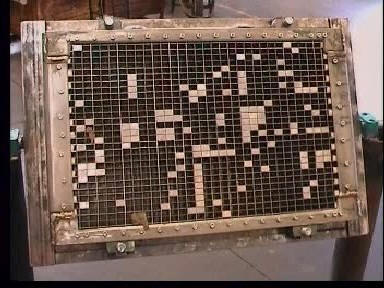

To improve the extraction we needed another tool. This time we produced a grid similar to the first one but with higher ”walls” and the hard base was deleted for a corresponding grid of rectangular wooden extractors of the same size as the bricks. The two parts were assemble together with metal bolts, allowing the extractor to freely slide inside the grid, removing the moulded pieces. This time the size of the grid was also grossly enlarged as to produce about 1,000 bricks in one go. The entire assembly was supported by a wooden frame.

The tooling worked perfectly well for not much than 10-15 thousand bricks, after which the humidity of clay caused the wooden extractors to swell and seize, rendering the extractor useless. This setback temporarily brought the entire project into a halt, but the job was started and the mould idea was good. All we had to do was producing a new tooling, based on the previous solution but manufactured all in metal.

We used 48 meters of 15×10 mm aluminium bars, cut to uniform length of about 10 cm high to make the extractor pistons while the grid was manufactured of 0,5 mm thickness AISI 304 sheet; the chassis was a welded steel structure. The up and down movement of the extractor pistons is actuated by means of a crank and a bicycle chain.

Proof-of-concept

Meanwhile we began to make the first walls, and for the start we choose a detachable part: the portico of the temple, experimenting with various bonding materials. The results were promising.

Nine months passed from the start of the project till this point. The reader may (rightly) think that producing the brick machine was a major undertaking, but the biggest problem which emerged during this period was the relationship between the workers. Everyone had his own ideas for the best solution to everything. Modellers are lone beasts with the habit of working entirely to their own standards. One of the biggest challenges had been to keep everybody quiet and focused on one current solution but the first successes and the problems we resolved boosted the sense of comradeship. Some very nice dinners catered directly at the battlefield and a few glasses of wine made the rest.

At this stage we had to manufacture a series of secondary tools, for example that to produce a frieze with a motif of repeating arches which runs along the perimeter of the church.

Continue to Part 2: Every Window Tells a Story

This article was originally published in IPMS Stockholms Magazine in June 2007