model by Magnus Löfqvist

text and photos by Martin Waligorski

After the death of King Charles II a succession dispute  developed between his brother, James VII of Scotland and II of England and his son-in-law, William of Orange. The entire history if this conflict is not within the scope of this article, suffice to say that in 1688 William became William III of England and James fled the country.

developed between his brother, James VII of Scotland and II of England and his son-in-law, William of Orange. The entire history if this conflict is not within the scope of this article, suffice to say that in 1688 William became William III of England and James fled the country.

In Scotland, which has officially accepted William as King William II of Scotland, there were substantial sentiments in favour of James VII. The term Jacobite became the name for his supporters. They ultimately lead to a rebellion, a war that had lasted on and off from 1689 to 1746. The most famous part of the conflict was the Jacobite rebellion of 1745. When Charles Stuart (a.k.a. Bonnie Prince Charlie) arrived in Scotland in 1745, most of the highland clans gave him their support. At the Battle of Prestonpans in September 1745 and the Battle of Falkirk in January 1746, the Highland Charge once again proved successful against the English army.

In the numerous battles between the 16th and the 18th centuries, the Scottish Highland Charge became synonymous with shockingly ferocious attacks. It had such a psychological power that often opposing units began to break before the charging Highlanders actually impacted their ranks. From the tactical point of view, however, they were unlike the regular army. While highly effective in close combat, the clan regiments were hard to control and regroup once enemy units broke. This prevented organized exploitation of successes. And if the enemy infantry managed to stand firm, the results could be a rout. This was about to happen soon.

By the time the two sides met again at Culloden Moor near  Inverness in the North of Scotland on April 16th, 1746, the English army had developed a new strategy against the Highland Charge. The infantry were put into three ranks. The front rank were ordered not to fire until the Highlanders were only twelve yards away. While the front rank reloaded, the second rank fired their guns. By the time the third rank had fired their guns, the first rank were ready to fire again. The infantry now used firelocks which were faster to reload than the previous matchlock guns. These guns were also fitted with bayonets so that even if some of the enemy were able to reach the English front-lines they were able to defend themselves against the broadswords of the Highlanders.

Inverness in the North of Scotland on April 16th, 1746, the English army had developed a new strategy against the Highland Charge. The infantry were put into three ranks. The front rank were ordered not to fire until the Highlanders were only twelve yards away. While the front rank reloaded, the second rank fired their guns. By the time the third rank had fired their guns, the first rank were ready to fire again. The infantry now used firelocks which were faster to reload than the previous matchlock guns. These guns were also fitted with bayonets so that even if some of the enemy were able to reach the English front-lines they were able to defend themselves against the broadswords of the Highlanders.

This time the English army did not run away when the Highlanders charged. Faced with the well-organised infantry that fired their guns in stages, very few Highlanders managed at all to reach the English lines. Unable to get dose enough to use their broadswords, some Highlanders even resorted to throwing stones at the English army. In only 45 minutes the battle turned to a disaster. Cumberland’s army devastated the Jacobites and Charles was forced to flee from the battlefield and hide.

This battle effectively marked the end of Jacobites, but there were even more severe consequences for the Highlanders. The battle was followed by a lengthy period of suppression in the Highlands marked by massacre and despoiling. The English army would kill any Highlander they could find that had been a member of the Jacobite army. Even Highlanders who had not joined the rebellion were slaughtered, women and children. The English army also destroyed the Highlander’s homes and took away their cattle. Unable to survive without their cattle, 40,000 Highlanders emigrated to America. Laws were also passed that made it illegal for Highlanders to carry weapons, wear tartan clothes or play their bagpipes.

And so the Culloden became the Highlander clans’ last charge.

The figure

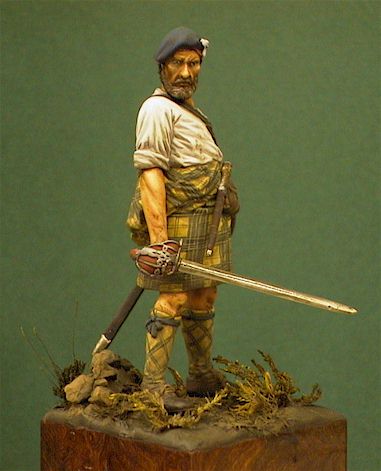

Magnus Löfqvist is the author of this 54 mm figure.  The figure itself is a white metal kit from Beneito Miniatures and represents excellent sculpting and level of detail. The figure was originally issued as Highlander del clan McDonald, batalla de Falkirk, 1746, but Magnus decided that the setting for his highlander was the fateful Culloden not Falkirk.

The figure itself is a white metal kit from Beneito Miniatures and represents excellent sculpting and level of detail. The figure was originally issued as Highlander del clan McDonald, batalla de Falkirk, 1746, but Magnus decided that the setting for his highlander was the fateful Culloden not Falkirk.

Magnus used artist’s oils for painting of the figure’s face, hair and skin parts. The clothing and the various accessories were painted with acrylics. The most challenging part of the project was the kilt, which was meticulously hand-painted.

The base was modelled from Milliput.

This article was originally published in IPMS Stockholm Magazine in August 2003.