I believe it goes without saying, but I’ll say it anyway: scribing panel lines on a model is a technique that requires some experience to get right. Four distinct issues arise in scribing a plastic model:

- Choosing the tool to use;

- Planning where to scribe;

- Guiding the scribing tool; and

- Making corrections.

My experience in using the techniques described here is restricted to aircraft, which is all I build, but I feel confident that the methods will be useful for other kinds of styrene and resin models as well.

Choosing the Tool

The best tool for scribing surface detail into plastic depends upon a variety of factors, the most important of which are the hardness of the styrene or resin and the complexity of the detail to be scribed. Art Murray points out that kits scribe differently due to the inconsistencies of the plastics used in kits. A simple solution: Use the unseen underside of an aircraft wing, car body or ship hull to practice a little. This exercise gives one a feel for the properties of the plastic used in the kit. Art especially recommends this when using the Micro Mark Plastic Scriber described immediately below, because the width and depth of lines scribed with this tool vary with the pressure exerted: the softer the plastic, the less pressure that’s needed.

The best tool for scribing surface detail into plastic depends upon a variety of factors, the most important of which are the hardness of the styrene or resin and the complexity of the detail to be scribed. Art Murray points out that kits scribe differently due to the inconsistencies of the plastics used in kits. A simple solution: Use the unseen underside of an aircraft wing, car body or ship hull to practice a little. This exercise gives one a feel for the properties of the plastic used in the kit. Art especially recommends this when using the Micro Mark Plastic Scriber described immediately below, because the width and depth of lines scribed with this tool vary with the pressure exerted: the softer the plastic, the less pressure that’s needed.

In general, I prefer to use a hook-shaped tool that is made especially for scribing plastic and can be purchased in the USA, for example, by mail-order from the Micro Mark hobby tool company. Actually, this tool is simply a curved dentist’s pick that has had its tip re-ground into a sharp plow shape. The main advantage of this tool is that it removes a tiny v-shaped ”ribbon” of plastic as the tool is pulled along a soft plastic surface, so no ”ridges” remain beside the scribed line to be sanded down. However, this tool does not work well on very hard plastic, because it cannot smoothly ”dig out” a ribbon in that situation, and it is difficult to manipulate around sharp corners or when creating intricate details.

Another basic tool for engraving surface detail into plastic is a steel machinist’s scriber that has a very sharp (preferably carbide or diamond) tip. It scratches instead of plowing, so it creates raised edges on each side of the line that must be removed with sandpaper or very fine steel wool; sanding debris must then be removed from the scribed line with a sharp pin. However, this tool is easy to manipulate around corners – inside a template, for example – and it works well on hard materials (because it was designed to make marks on metal!).

A pointed (e.g., No. 11 X-Acto) knife blade held in a slender handle also is helpful in some situations, because the tip of such a blade can be manipulated very precisely. However, a knife blade’s disadvantages are that it tends to wander along the path of least resistance through a plastic surface, and it tends to cut too deeply. In situations where a pointed knife blade seems best, I either use the back (rather than the sharpened) side of the blade tip, or I scribe the line very lightly once or twice with the sharpened side of the tip to establish a guide and then rotate the knife in my hand before going over the line several times again with the back of the blade tip. Kevin Martin points out – and I agree – that an old, dull No. 11 blade works best. Like a machinist’s scribing tool, a knife blade creates raised edges on each side of its line that must be removed with fine sandpaper or steel wool. Incidentally, a pointed blade is the only tool that can be used for free-hand scribing – but this is very difficult and should not be attempted without years of scribing experience.

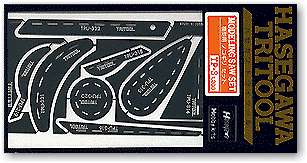

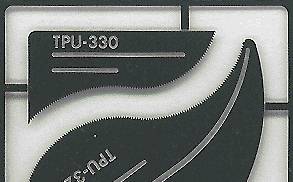

Two very helpful sets of thin, photoetched razor-saw blades with various concave, convex, and straight edges that are especially handy for special tasks such as scribing around sharply convex surfaces – e.g., over the top or bottom of a fuselage or around the leading edge of a wing – were manufactured by TriMaster some years ago and are now produced by Hasegawa. These saws aren’t sold in the US, as far as I know, but they can be purchased by mailorder from HobbyLink Japan

I find the second of these sets (HLJ’s item HSGTP-4) to be the more generally useful. Simon Craven points out that similar blades – though none with a concave edge – can be obtained from Airwaves (ED Models), in Shirley, West Midlands, UK. On the other hand, Lee Rouse and Woody Vondracek recommend a trick proposed by Bob Steinbrunn in FineScale Modeler. Using a Dremel tool, cut small notches across the sharp edge of an old No. 11 blade. This gives the blade the appearance of having small saw teeth. Then insert the blade into its handle and cut/saw across the surface to be scribed.

Planning

The basic rule here is simple: Think, draw and look before you scribe.

First, decide where to scribe lines. Usually you have two options: where you found raised panel lines on the kit, or where scale drawings show panel lines. Drawings often disagree about the locations of panel lines in my experience, so consult photographs whenever possible. However, you’ll probably have to make at least some arbitrary decisions, because at least some panel lines probably won’t be visible in the photos you have.

Next, use a sharp, soft (e.g., No. 2) pencil to draw every panel line that you intend to scribe. I prefer to prime my model with light gray paint before drawing the lines. This isn’t absolutely necessary, but it makes the penciled lines easier to draw and easier to see after they’re drawn. You can sketch the lines lightly at first if you wish, but it’s important eventually to draw each line carefully using a straightedge – and perhaps templates, as described in the next section. Wherever you find that you’ve drawn a line in the wrong place, erase it and redraw it correctly. It doesn’t matter if pencil smudges make your model dirty at this point: keep drawing, erasing, and re-drawing until you think you have all of the panel lines drawn perfectly.

Walk away and do something else. Then come back in an hour – or the next day – and look carefully at your model from as many different angles as possible. I can almost guarantee that you’ll find some of the lines you drew to be slightly misaligned if you look long enough. And, of course, you’ll have a long time to look at your model after it’s finished! Getting lines parallel or perpendicular – when they should be – is particularly difficult, and alignment is much more easily judged by eye than by any measurements. If you’re working from scale drawings, also compare the penciled lines to your scale drawings and make corrections as necessary.

Now keep repeating the previous paragraph’s tasks until you can’t find any more errors in your penciled lines.

I don’t want to make this planning step seem more difficult than it really is, but I can almost guarantee that ”Murphy’s Law” will ensure some misaligned and/or incorrectly-located scribing if you’re not careful here. Correcting scribed lines is a lot harder than correcting penciled lines. Trust me.

Art Murray points out that when raised panel lines are sanded away from a styrene model, a line of lighter color plastic will remain where the old line used to be. This line can then be used as a guide for the new scribed panel line if desired. Chris Bucholtz notes that this trick works particularly well on kits molded in silver plastic. Jennings Heilig adds that raised panel lines that have been sanded off can be accentuated – particularly on dark plastic – by airbrushing them lightly with either lacquer thinner or super glue accelerator; neither of which should be inhaled!

Guiding the Tool

It’s very difficult to guide a scribing tool accurately free hand, so the tool should be moved along a smooth, hard, raised edge whenever possible.

For straight lines, a thin, slightly flexible metal strip or ruler works best. Note that except in a few very simple situations, ordinary metal rulers aren’t very useful for scribing, because they tend to be too thick and too rigid. Some thin stainless steel strips – usually about 5 mm (i.e., 3/16 inch) wide – have been sold specifically for this purpose and I own several, but I don’t know whether any of these are currently available in stores or by mail-order. You can make a similar scribing guide that is almost as good simply by purchasing a cheap steel carpenter’s measuring tape, of the type which rolls up inside a container approximately 5 cm in diameter, breaking open the container, and cutting off 10-30 cm (i.e., 4-12 inch) segments of the steel tape. Having several different lengths is handy, and you can easily throw away and replace any pieces whose edges become damaged.

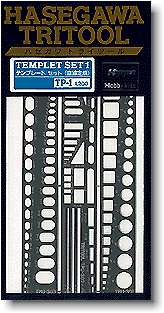

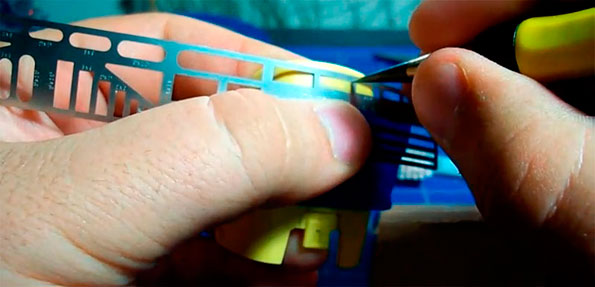

Another kind of metal guide has been sold specifically for the purpose of scribing geometric shapes onto plastic models. Mine were manufactured by TriMaster some years ago and are now produced by Hasegawa. Like the saws mentioned above, these aren’t sold in the US as far as I know but can be purchased by mailorder from HobbyLink Japan. Art Murray points out that Verlinden currently markets scribing templates for both 1/72 & 1/48 scale aircraft; he also notes, from personal experience, that they have very sharp edges and should be used with caution!

Templates of this kind are basically thin stainless steel sheets or strips that contain circular and/or rectangular openings of different sizes; the outer edges can be used to scribe straight lines, and the edges of the openings serve as guides for scribing circles and ”hatches.” A similar, more widely available guide of this type is a draftsman’s erasing guide, which is a thin stainless steel rectangle, often about 8×10 cm (i.e., 3×4 inches) with rounded corners, which has variously shaped openings cut through the sheetmetal. Plastic draftsman’s drawing templates that contain circular or rectangular openings also can be helpful, but they’re more awkward to use because they’re thicker. As an aside, I’ll mention here that plastic draftsman’s circle templates are very useful as masks for spray-painting round national markings onto clear decal stock – just block off the circles surrounding the one of interest with masking tape.

Guides of the kind I’ve described so far aren’t very useful for irregularly curved lines like those on the underside of a Spitfire or P-47 fuselage, for example. In these situations, the best approach I’ve found is the following:

Define the desired line with the edge of a sharply-cut narrow strip of flexible masking tape. Do not use the soft Scotch office tape;

Scribe lightly a few times along the edge of the masking tape with the tip of a machinist’s scriber or rather dull X-Acto blade, just deeply enough to serve as a guide for careful subsequent scribing. Be very careful, because the edge of the masking tape is thin and soft.

Gradually deepen the established line by repeatedly going over it with one of the tools I’ve described above.

Kevin Martin adds that to rescribe sharply curved lines such as those around a P-47’s wing fillet, he burnishes masking tape over the area to be scribed and then marks the line with a pencil. After removing the tape, Kevin applies it to a flattened piece of thin aluminum sheet cut from a beverage can. He cuts the shape with scissors and cleans it with a flexible file – or ladies’ fingernail polishing board. This can then be used as a scribing pattern. Woody Vondracek recommends making templates from .010 styrene, which is easy to cut and will last through a couple models. He puts a strip of 3/4 inch white artist tape over the curved lines (before sanding) and rubs a pencil over it to get the shape. He then sticks the tape on the styrene and cuts it to shape. A French curve helps to get smooth curved lines.

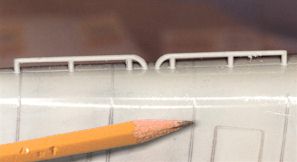

A particularly difficult task in scribing plastic model airplanes is getting neat and parallel circumferential fuselage panel lines (i.e., panel lines that go around the fuselage), because it’s very difficult to hold a metal straight edge at the correct location, and it can be difficult to avoid waves and wiggles if you apply strips of masking tape as a guide.

By far the best approach I’ve found to this problem, which I learned from my friend Wally Splitt, employs the rather rigid, colored plastic embossing tape – e.g., Dymo brand – that is sold for making embossed self-adhesive labels. Buy the narrowest (usually 1/4 inch – about 6 mm) width of this tape – in a bright color, if possible, so you can easily see where to scribe. Cut a strip long enough to go around your model’s fuselage; cut this strip in half with scissors somewhat raggedly along its length; remove the protective backing from the half strip so that the tape’s adhesive is exposed; and apply the half strip of tape around your fuselage so that its straight edge is where you want the desired panel line. If the fuselage is tapering along its length at the location where circumferential line is to go, the tape can be applied most easily on the side of the line toward which the fuselage becomes smaller in diameter. You can then scribe the line as you would if masking tape were serving as a guide. The advantages of the plastic embossing tape in this situation are that (i) it’s flexible enough to wrap around your fuselage but rigid enough to help you avoid waves when you place it along the desired panel lines, and (ii) it’s thick and rigid enough so that you don’t have to be quite as careful in your initial light passes with your X-Acto knife as you must be with masking tape. The tape’s adhesive is crucial in keeping the guiding edge firmly in place but it wears out quickly, so don’t be ”penny wise and pound foolish”: use a new piece of tape as soon as the old adhesive starts to weaken – usually after only one application.

An entirely different approach is to use a set of curved metal templates that were produced initially by TriMaster and are now manufactured by Hasegawa. Personally I don’t find them as helpful as the other ”Tri-Tool” scribing aids.

Making Corrections

No matter how carefully you’ve tried to scribe your lines, you’ve probably made at least a few mistakes at this point – I make a lot – so you’ll have to correct those errors.

After you’ve scribed all of the lines you want, wash your model gently with lukewarm water to which you’ve added a little mild dish washing detergent. By the way, always use the kind used for washing dishes by hand – not the kind used in automatic dishwashers, which is harsh and contains bleach. Scrub gently with a soft toothbrush and lots of water to remove all pencil smudges from the model’s surface and all debris from the scribed lines.

When the model is completely dry – a hair drier used carefully on its lowest setting can speed things up here – apply a thin coat of light gray primer. Then after this paint is dry, carefully inspect your model from all angles in good light, and use a soft pencil to circle the locations of all flaws in the scribing.

Fill each marked flaw with the minimum required amount of a fine-grained, strongly-bonding plastic-modeling putty. I prefer Dr. MicroTools red putty for this purpose, and I apply it with the tip of a No. 11 X-Acto blade. In situations where you want to eliminate a scribed line that was in the wrong place or that extended too far (e.g., past a corner), simply fill the line with putty or thick superglue, very slightly above your model’s surface to allow for shrinkage. In situations where a scribed line needs to be narrowed or made less deep, fill the line, use putty, let it harden partially, and then carefully rescribe through the center of the filled line with a No. 11 X-Acto blade. In situations where your scribing tool had slipped and a ”false branch” needs to be eliminated, use a combination of the two previous techniques. Partially hardened putty is much easier to rescribe than fully hardened putty, and you’ll quickly learn by experience how much to let the putty set up before you rescribe through it.

After the putty or superglue has dried completely, carefully wet-sand each corrected flaw with 600-grit wet-or-dry sandpaper. Then return to the top of this section and repeat the process until you can’t find any more flaws in the newly-primed model.

Overview

The described techniques require some practice to get right – practice on an old or unimportant model first.

The sequence of steps that I’ve described here can be a bit tedious for a large model that must be rescribed completely, but it really isn’t difficult, and the entire process can be accomplished rather quickly when only a small amount of touch up scribing is needed to repair a few engraved panel lines that were damaged during kit construction. Scribing a model can even be relaxing, if you aren’t in a hurry

© Copyright Charles E. Metz 1997, 1999