by Joachim Smith

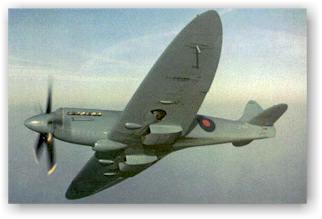

S31 – Supermarine Spitfire PR Mk XIX

The Spitfire PR Mk XIX was the last of the specialised photo reconnaissance Spits and the only one with a Griffon engine, being delivered to the RAF from mid-1944 to shortly after the end of WWII.

Classic Charles Brown photo of Spitfire PR XIXThe Mk XIX was unarmed and could carry two vertical cameras and/or one oblique camera in a heated compartment aft of the cockpit. It had a top speed of 716 km/h, a cruising speed of 430 km/h and a ceiling of about 13000 metres. With an external auxiliary tank, the total fuel capacity was 1563 litres and top range 2250 kilometres. The cockpit was pressurised with the aid of an engine-driven blower.

In 1945, the Swedish Air Force had a pressing need for a single-seat reconnaissance plane. As a stop-gap measure, a number of obsolete J9 fighters (Seversky P-35A) were converted and transferred to the F11 reconnaissance wing at Skavsta in Nyköping.

In 1948, the cold war prompted an urgent upgrade of the Swedish AF, but the planned PR version of Sweden’s indigenous swept-wing jet fighter, the SAAB J29 ’Flying Barrel’, was delayed since the fighter version had priority.

As an interim solution, in 1948 a total of 50 surplus PR Mk XIX Spitfires were bought from England at a bargain price and assigned to the F11 wing with the Swedish designation S31. The recce wing was thus equipped with a plane which flew faster and higher than any of the Swedish AF fighters in service at the time. The S31 was instrumental in developing new AF reconnaissance tactics.

The last S31 was retired from Swedish service in August of 1955 and, in an act of bureaucratic vandalism, every single Spitfire was either scrapped, used for target practice or relegated to fire fighting drills. Still, an immaculate S31 in Swedish colours is currently on display in the Swedish Air Force Museum at Malmen near Linköping.

The S31 in the Swedish Air Force Museum

Since all the S31:s were destroyed, the Air Force Museum had a gaping void in its collection which was not filled until S31 number 51 was ’rolled in’ on March 15th 1989.

Starting life as PM627, this Mk XIX had a chequered career, having flown in the RAF from late 1945-51. It served in the Indian Air Force between 1953 and -57 and was then displayed in the Indian Air Force Museum until it was bought in 1971 by the Canadian Fighter Pilots Association.

Located by the indefatigable Mr. Sölve Fasth of the AF Museum, this Spitfire was acquired in 1982 through a complex and costly barter deal. The Museum had to relinquish no less than one Tp79 (DC-3), one J34 (Hawker Hunter), one AD-4 Skyraider and two and a half (!) SAAB A32 Lansen attack jets.

In return, the Museum got one rather dilapidated Mk XIX, lacking its engine, mainwheels, most of the cockpit equipment, windscreen and canopy. The complicated and extremely thorough restoration took some 10 000 man hours, put in by volunteer Spitfire enthusiasts from 23 to 76 years old.

mainwheels, most of the cockpit equipment, windscreen and canopy. The complicated and extremely thorough restoration took some 10 000 man hours, put in by volunteer Spitfire enthusiasts from 23 to 76 years old.

Supermarine Spitfire PR Mk XIX (S31)

The museum’s example is a subject of the photo essay. Since there are many photographs, the material has been divided into sections below.

Fuselage

Airframe and camouflage

S31 PM627 resplendent in the Swedish AF Museum.

The massive engine cowling is a bit exaggerated by the wide angle lens, but the shape of the cylinder bank covers is shown to advantage. Photo: Joachim Smith

The actual shade of the PRU Blue paint work has caught some (unfounded) criticism, most likely as a result of the greenish floodlighting in the Museum, which tints the colour a murky greenish nuance, while the flashlight of this picture seems to make it rather too bluish.

The subtleties of the wing radiator shape are quite well shown from this angle. Photo: Joachim Smith

This closeup, taken in ambient light, shows how tricky photographic reproduction of the PRU blue colour can be.

The curved windscreen, the whip antenna, the oblique camera port and the F11 wing griffon badge are shown to advantage. Photo: Joachim Smith

The F11 wing griffon badge is ’handed’, with the griffon always looking forward.

Note the subtle shape of the canopy and the smooth finish of the metalwork.

Photo: Joachim Smith

The oblique camera port has an optically flat glass panel. There is no camera port on the starboard side.

Of note is also the cover over the canopy rail. Photo: Joachim Smith

This is what fabric covered surfaces look like in reality – no sag between the ribs and no sack weave pattern! The leather tail wheel oleo cover and the clear navigation light fairing are noteworthy.

PM627 has been given the number ’51’, since it is the 51st Spit in the Swedish AF inventory. Photo: Joachim Smith

Griffon nose

Subtleties of the Rolls-Royce Griffon engine cover show up here.

The twist of the prop blades makes their true shape deceptive. Note also the flat yellow pin sticking up from the wing – this is the mechanical gear down indicator. Photo: Joachim Smith

On the port side of the engine cowling, below the exhaust stack, is the air intake for the engine-driven cockpit pressurisation. The Rotol prop blades lack their customary metal leading edge covers. Photo: Joachim Smith

Details of the prop blade roots and markings will help the reshaping of kit propellers. The cockpit air intake has a separate FOD screen fitted in front of it. Photo: Joachim Smith

Wing and undercarriage

This is what the port navigation light looks like and, slightly blurred, the airspeed pitot intake. Photo: Joachim Smith

From this angle, the rounded fillet fairing the radiator housing into the wing is clearly visible. Also noteworthy are the landing gear retaining eyelet and the fuel booster pump cover bulge, which extends to the gear cover.

Photo: Joachim Smith

The vertical intake lip of the radiator housing is at right angles to the underwing surface. The radiator itself is recessed at an angle with the aft end deeper in the wing; hence the radiator face is not parallel to the intake. The bulge is the underwing fuel booster pump fairing.

Note also the white anti-slip marks painted over the tyre and rim. Photo: Joachim Smith

The flashlight reveals the internal structure of the engine supercharger air intake. The gull wing shape of the wing root is evident from this angle, as is the gear cover extension of the booster pump bulge.

Two drop tank retaining hooks can bee seen in the rear. Photo: Joachim Smith

The starboard radiator from an unusual angle.

Of interest is also the mainwheel brake line and the tyre pattern, obviously difficult to reproduce on a scale model.

Photo: Joachim Smith

Closeup of the starboard hook where the trailing edge of the auxiliary fuel tank rested. The hooks ensured clean separation when the tank was dropped. Photo: Joachim Smith

Cockpit

The cockpit interior looks much like any other Spitfire Mark, the most obvious exception being the natural metal camera control box replacing the gun sight. Note the padded backrest of the pilot’s seat. Photo: Joachim Smith

A closeup of the camera control box. Conspicuous by its absence, the magnetic compass had not yet been installed below the dashboard when this picture was taken in August of 1990. Photo: Joachim Smith

Note the extra fairing on the trailing edge of the sliding canopy and the internal support rod for the head armour. Mounted on the armour is a perspex tube, housing silica gel for removing moisture from the cabin pressurised air, which could otherwise cause misting. Photo: Joachim Smith

The clear perspex tube allowed for easy inspection of the silica gel crystals, which change colour when they become saturated with moisture and have to be replaced. Note the arrangement of the Sutton harness shoulder straps and the pressure bulkhead at far right. A glimpse can be seen of one of the three oxygen tubes behind the seat.

Photo: Joachim Smith

This view from starboard shows the attachment clips of the silica gel tube and two of the three oxygen tubes behind the pilot’s back armour. Photo: Joachim Smith

Detail of the rear end of shoulder straps.

Detail of the rear end of shoulder straps.

The stencilling on the oxygen tubes reads:

USE NO OIL OR GREASE THEY CAUSE EXPLOSIONS

Photo: Joachim Smith

Camera equipment

The business end of one of the two camera types used in the S31, the vertical SKa 10 (SKa being the acronym for SpaningsKamera, meaning ’reconnaissance camera’).

The business end of one of the two camera types used in the S31, the vertical SKa 10 (SKa being the acronym for SpaningsKamera, meaning ’reconnaissance camera’).

Photo: Joachim Smith

The SKa 10 was also used in the twin-engine SAAB S18 and later in the S29 recce version of the Tunnan (’Flying Barrel’) jet fighter. Photo: Joachim Smith

The film magazine of the SKa 10 could hold some 500 18x21cm pictures on a 100 metre roll of perforated film, 23 centimetres wide.

Photo: Joachim Smith

Published references

Much has been written about the Spitfire, but two books especially for the Mk XIX enthusiast should be mentioned.

The obvious first choice is S31 Spitfire Mk XIX i den svenska flygspaningen by Axel Carleson which covers the the PR Mk XIX in Swedish AF service and also includes notes on the restoration of the Museum S31. The book is jam-packed with unique contemporary pictures (some in colour), cockpit and camera installation drawings and is generally a treasure trove for the modeller. The text is in Swedish, sadly without even a summary in English for international readers. Still, the excellent illustrations make it worthwhile even if you do not understand the language. It was published in 1996 by Östergötlands Flyghistoriska Sällskap, ISSN 1102-7088.

’Born Again’ Spitfire PS 915 was published in 1989 by Midland Counties Publications, ISBN 0 904597 74 1. The booklet (48 pages) covers the history and restoration to airworthy condition of PR Mk XIX PS915, now belonging to the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight. The many photos and detail views make this publication invaluable to modellers.

©1998 Joachim Smith

This article was originally published in IPMS Stockholm Magazine in August 1998.