Photos by Graeme Adamson and Charles Hugo

Text by Martin Waligorski

Surviving samples of the world’s first operational jet fighter are rare enough; of over 1500 Messerchmitt Me 262s produced there are only eight aircraft left today, or ten if you count the two post-war Avia S-92s. One of the survivors was presented on these pages before (see our previous feature Me 262 in Detail), but now is the time for a true rarity – the world’s only existing Me 262 night fighter from the South African National Museum of Military History in Johannesburg.

The production two-seater variant of the Messerschmitt’s jet fighter, called Me 262B-1, was devised solely for conversion training purposes. For a fighter pilot accustomed with the piston-engined aircraft the Me 262 was a vehicle of a different age. The tricycle undercarriage, twin engines, completely new type of propulsion notwithstanding the temperamental throttle control – all contributed to the need of conversion trainer with instructor in the rear cockpit. As was the accustomed practice, two-seater machines were not to be built new but converted from fighter models. About 120 machines of this variant were finished during 1944 and 1945.

Initially, the idea of a night-fighter 262 was developed independently by Messerschmitt as the Me 262B-2. It was to have a longer fuselage accommodating the two crew, internal fuel tanks with the capacity comparable to that of a single-seat variant, and a Berlin radar antenna hidden inside the modified nose cone. However, by the end of 1944 the war situation deteriorated so rapidly that it was realized that an interim solution must be found before the B-2 could reach production status.

Thus some of the existing trainer machines were converted once again to interim model nightfighters becoming Me 262B-1a/U1. The conversion comprised a FuG218 radar with operator occupying the rear cockpit. Before the collapse of German defences, only a handful of this type reached operational use with a single unit, 10./NJG11 at Magdeburg.

The hero of our story started its career as Werknummer 110305. It was flown operationally at 10./NJG11 by Kurt Welter. Whilst at this location it carried a red number 8 outlined in white, and camouflage of grey mottle over all-black undersurfaces. This aircraft has been widely documented in books and numerous colour profiles.

So how did it end up in South Africa?

Together with other aircraft of the unit, Red 8 was surrendered at Schleswig. The two-seater aircraft were considered a prized booty by the British, who collected three flyable machines for evaluation purposes. The other two were Red 12, werknummer 111980, (later destroyed in a gale in 1947) and Red 10, werknummer 110635 (scrapped already later the same year).

On 18 May 1945 Red 8 was ferried to Gilze-Rijen and then to RAF Farnborough in the UK for evaluation. It was subsequently used for radar and tactical trials starting from July the same year. It carried the RAF serial VH519.

After completed trials, Red 8 was shipped to South Africa on 23 February 1947, arriving at Cape Town on 17 March. Amazingly, it survived in storage until the late-1960s when it was taken over by the museum.

This important aircraft was restored for display in 1971 and has been a crown exhibit of the Johannesburg museum since 1972.

Me 262B in detail

The sizeable photographic material of this walkaround has been divided into the following sections:

The airframe, engines, and canopy

The object of our photo essay as it looked in May 1945, shortly after being handed over to the British. The paint scheme is still the original 10./NJG11 pattern.

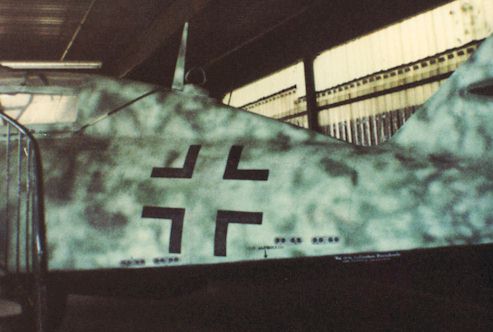

…and here it is today residing at the South African National Museum of Military History in Johannesburg. During the recent years, the museum did a commendable restoration job on this aircraft so that even the paint scheme is a faithful reconstruction of the original pattern.

As can be seen, the aircraft is stored under the open shed which unfortunately makes photography very difficult. Because of the high contrast between the sun and shadow areas it is almost impossible for the camera to make a well-exposed overall picture of the aircraft. The authors do not apologize for this as the same nasty light effects can be seen on photographs of Red 8 coming from other sources.

Photo: Graeme Adamson

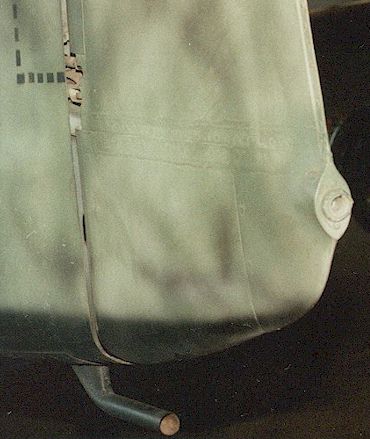

Looking at any full-size Messerschmitt fighter of the era, it is worth paying attention to the quality of the surface finish. It was invariably excellent with very nice flush-riveted skin and neat, almost invisible panel lines. Messerchmitt has perfected this production technique as early as mid-1930s with their Bf 108. For the high-speed airframe of the 262, the Messeschmitt’s technology came very handy contributing to the outstanding aerodynamic performance of this aircraft.

Photo: Charles Hugo

The major difference of the B variant was, of course, the canopy. Actually, the remainder of the airframe was virtually identical to the Me 262A, so that the majority of photo material contained in this essay applies equally to both types. Photo: Charles Hugo

The front and rear portions of the canopy opened independently. In a typical Messerschmitt fashion, the heavy canopy sections were hinged to the right and required considerable manual force to lift. Note the retaining wire and spring preventing the rear canopy from tipping over, and a massive handle attached to its inner frame Photo: Charles Hugo

The windscreen was identical to that of the Me 262A. Photo: Charles Hugo

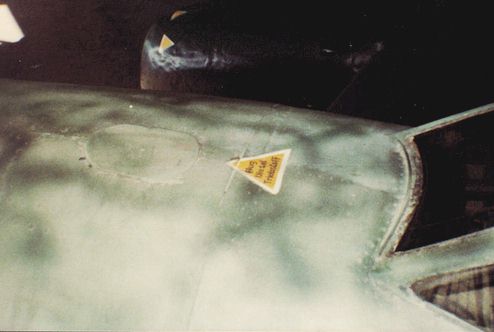

Another fuelling point in fromt of the windscreen covered with an elongated lock and market with yellow triangle stencil stating Flug Diesel Triebstoff – aircraft diesel fuel. Photo: Graeme Adamson

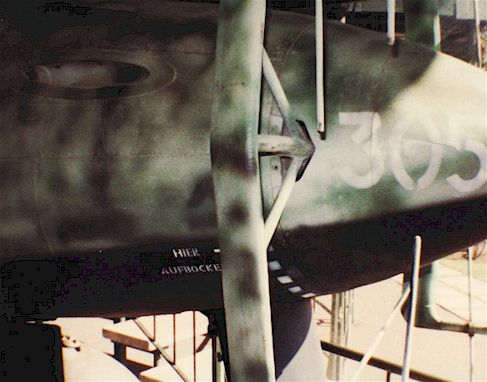

As the second cockpit was installed in the place normally occupied by the main fuselage fuel tank, the twin-seater Swallow lacked sufficient fuel capacity. To offset this, most aircraft flew with permanently attached external fuel tanks like the one shown here. It was carried on the standard Wikingerschiff pylon, the same as used for bombs on the JaBo versions of the aircraft. Its name came from the aerodynamic shape remaining of the ancient Viking ships.

Photo: Charles Hugo

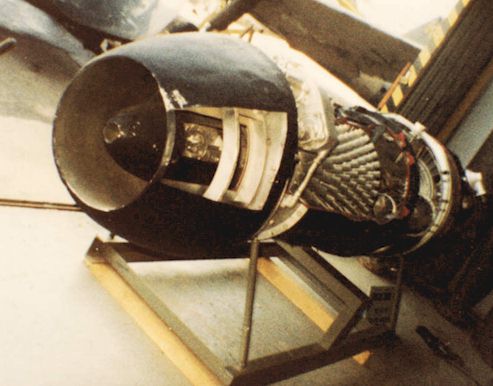

A peek into the front opening of the Jumo 004, showing the front turbine.

The visible central cone of the jet housed a gasoline-powered Riedel starter engine. This engine, which produced 10 horsepower at 6,000 rpm, had its own electric starter motor, but for emergencies it also had a pull starter in the nose cone, with pull string protruding through the visible circular opening. On some close-up photos of the 262 a ring handle of the pull starter can be seen residing in the opening, but this detail appears to be missing on the Johannesburg machine. Photo: Graeme Adamson

The business end of the Jumo turbojet. The power of the jet efflux could be regulated by the moveable rear cone, at the time nicknamed die Zwiebel (the onion) because of its shape. Photo: Graeme Adamson

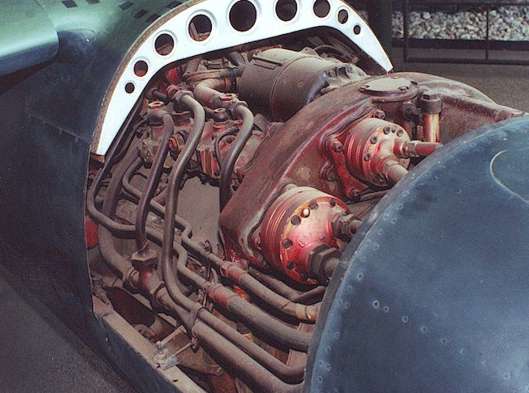

The cutaway of the Jumo 004 and the engine nacelle clearly illustrates its principle of operation. The engine was designed by Junkers engineer Anselm Franz. Bringing the 004 design from the concept to production in a span of four years was a pioneering achievement matching that of the Messerchmitt itself.

The engine specifications were deliberately kept conservative to allow for timely resolution of the numerous other development problems with this revolutionary powerplant. As is widely known, the 004 was dogged by unresolved teething troubles, particularly short between-service life and a tendency for flame-out during rapid throttle movements. In the end, it was small and efficient, but developed less power and was nowhere near as reliable as British jet constructions of the period.

The Jumo 004 compressor was an eight-stage unit with an outer casing of uniform diameter. The diameter of the intake was 20 inches. The upper forward cowling contained two annular gas tanks, containing fuel for the Riedel starter and the starter fuel for the combustion chambers. Photo: Charles Hugo

At the upper front of the nacelle was one of the many detachable service panels surrounding the engine, here revealing more details of the engine installation.

Photo: Charles Hugo

Radar, armament and other night fighter equipment

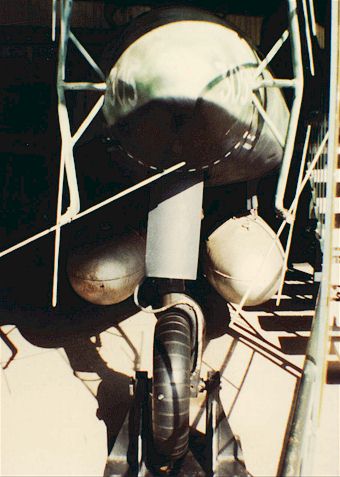

Dramatic view of the aircraft’s nose adorned with large radar antennae. Modellers will find this view helpful when bending and positioning those photoetched antenna parts. On the subject of photoetch, note that the real antenna braces are of circular (small) or aerofoil (large braces) section.

Dramatic view of the aircraft’s nose adorned with large radar antennae. Modellers will find this view helpful when bending and positioning those photoetched antenna parts. On the subject of photoetch, note that the real antenna braces are of circular (small) or aerofoil (large braces) section.

Photo: Graeme Adamsson

The author believes that the two extra diagonal braces holding the radar antennae were added by the British after a taxiing accident damaged the radar array. Anyway, they cannot be seen on the (somewhat blurry) wartime photos of the Red 8 and other 10./NJG11 machinenes. Photo: Graeme Adamson

Red 8 had a full complement of four 30mm MK 108 cannon, but it is believed that some night fighter Me 262s flew with only two cannon to compensate for the extra weight of the radar equipment. The cannon are unfortunately no longer in the aircraft, but all the feeds, spent cartridge chutes and electrical wiring on the rear bulkhead are in place.

A noteworthy detail is also one of the two circular stiffening braces running along the top of the cannon bay.

Photo: Charles Hugo

Inner detail of the cannon bay cover (starboard side). Photo: Charles Hugo

The distinctive and elegant triangular fin of the 262 is shown to advantage here. The ruder and elevator were mass-balanced, which was another one of Messerschmitt’s ”usuals”. Photo: Graeme Adamson

Besides the forward-looking radar equipment, the night fighter was to be equipped with a tail-warning FuG 218 Neptune radar. For some reason, this was never fitted to the operational aircraft and the only visible sign of the original intention was this antenna mounting pipe under the rudder. Photo: Charles Hugo

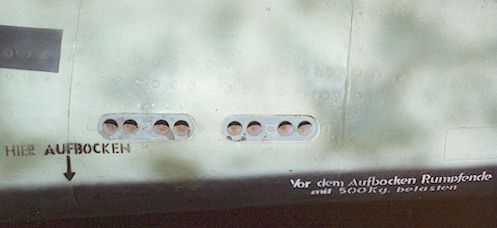

The port rear fuselage of the night fighter variant featured four sets of flare chutes, as compared to two of the Me 262A or the B-1 trainer.

Note also the radio mast immediately behind the cockpit and the D/F loop mounted on a teardrop fairing.

Photo: Graeme Adamson

Details of the rear flare chutes and some stenciling. Photo: Charles Hugo

The mass balance of the port elevator. Photo: Charles Hugo

Interior details

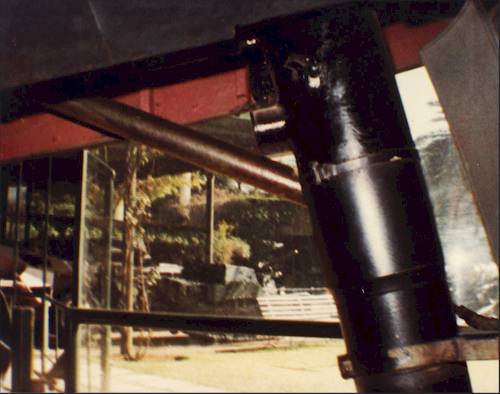

Main undercarriage unit seen from the front. Photo: Charles Hugo

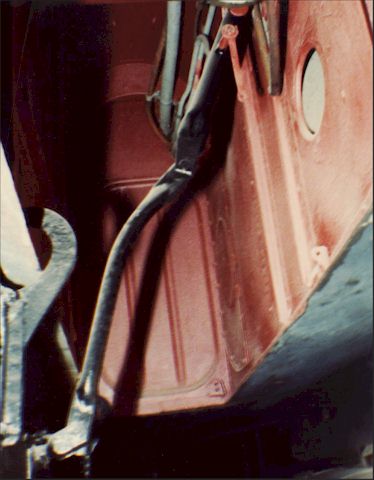

This photo showing the main wheel well gives some idea about its internal structure and the electrical wiring present there. Photo: Graeme Adamson

More detail of the main wheel well, this time looking towards the main leg pivot point with hydraulic retraction jack visible to the right. Photo: Graeme Adamson

Close-up of the front undercarriage leg. Photo: Graeme Adamson

…and the rear part of the forward wheel well. Photo: Graeme Adamson

The forward cockpit of the Johannesburg aircraft is in almost-original condition including all the wear accumulated during the years of service and display. The leather seat cushion is original, as are the seat belts. Photo: Graeme Adamson

Port side of the cockpit with a few missing switches, and the control stick. Photo: Charles Hugo

Instrument panel in almost pristine condition! Photo: Charles Hugo

The rear seat is also there, followed by a massive fuel filler cap on the rear decking marked with the usual yellow triangle. Photo: Graeme Adamson

Unfortunately the radar electronics disappeared from the aircraft early during its career. Presumably the radar was removed already before the flight trials in the UK to be tested separately. What’s left is the rack in front of the rear cockpit which used to hold the FuG218 receiver and its CRT display. Photo: Graeme Adamson

This article was originally published in IPMS Stockholm Magazine in April 2002.